The Long Read #1: Avalanche forecasting lore.

21st February 2018

Now that the snow has at last settled down I thought it might be a good time to introduce occasional magazine-type pieces into the blog. They’ll be a bit of a longer read and I hope they’ll shed some light on what we do, how we do it and the people (past & present) who carried it out, and maybe those who’ll be carrying it out in the future.

This Longer Read is a little technical but not so techy as to put off the general reader, I hope. I know you like pictures so there’ll always be one or two to add some visual interest.

Of course, there’s something about current conditions but that’s at the end of what follows.

Avalanche forecasting lore.

lore (noun) -Â a body of traditions and knowledge on a subject or held by a particular group, typically passed from person to person by word of mouth.

A close relative of mine was quizzing me recently about avalanche forecasting. He has an engineering and scientific background and speculated that there must be a few ârules of thumbâ in avalanche forecasting, in the same way as there are in some of the physical and/or material sciences.

It was a good question and jogged a hazy memory I have of a keynote presentation given to a training group I was part of in Canada back in the 1990s. This particular module of the training programme was delivered by Dave McLung who was, and remains, one of the pre-eminent academics in snow science in North America. So, I paid attention! Notes were taken. And in order to answer my inquisitive relativeâs questions, I dusted off my old notebook and just about managed to decipher the hastily scrawled bullet points made over two decades ago. Iâve expanded and simplified them a bit so that they make sense to a lay reader. They went something like this:

- The snow is stable.

The snow is stable most of the time when considering normal triggering forces.

I remember asking the late Blyth Wright about this and he concurred, remarking that statistically it only avalanches 20% of the time during the Scottish winter months. Bear in mind though that this may mean in reality an avalanche cycle lasting several consecutive days then nothing for a couple of weeks, and not necessarily a simple âeven distributionâ of avalanche events.

Of course, this ârule of thumbâ is of limited use to the average mountain user considering their mountain sport options for tomorrow since the avalanche problem is dynamic in both time and spatial distribution. For avalanche forecasters, stepping back a little and taking an overview, itâs quite a handy credo but can never be used alone.

- There are only two types of situations where there is seasonal snow cover: absolute instability & conditional instability.

âAbsolute instabilityâ is when thereâs widespread natural avalanche activity and this occurs for only a few hours each winter.

Most of Scotlandâs avalanches are ânew snowâ avalanches occurring during, or immediately after, snowfall or drifting. Difficult to believe itâs just a few hours each season, but these type of avalanches are after all very short-cycle events.

âConditional instabilityâ is where a trigger of variable size is required to initiate avalanching now or at some time in the future.

Ever wondered why there can be times when itâs âConsiderableâ avalanche hazard for days on end but there are no avalanches reported? Here lies the answer. Itâs almost always related to the prevailing weather conditions for that part of the winter giving rise to instability that may persist for a long time. (An Alpine – European, N.American et al – snowpack can maintain instability even longer.) The higher the instability, the smaller the trigger required to initiate an avalanche; lower instability needs a much bigger trigger. So, when itâs âConsiderableâ it doesnât necessarily mean itâs going to avalanche, it just means itâs pretty unstable and needs a relatively small trigger to produce a slide. If the trigger isnât big enough, the unstable snow will just sit there.

Have a look at the âAvalanche Hazard & Travel Adviceâ table on the SAIS main website for further details and scaling.

Also, bear in mind that all snow will slide on a slope of 15 degrees or steeper. If the trigger (force) is big enough it will avalanche no matter how stable you consider the snow to be, though that may require an earthquake, explosion from a thermo-nuclear device or something.

- The ânot normalâ.

Itâs bad enough dealing with what are considered ânormalâ weather conditions but uncertainty in forecasting is increased when there is an unusual combination of factors.

Uncertainty in these circumstances is to be expected since each forecaster carries a series of memories of the interplay of ânormalâ weather factors (often juggling very subtle combinations of these factors, too). Anything outside this personal historical database of normal events can leave you perplexed when forecasting, to say the least.

Itâs interesting that when visiting forecasters from Europe or North America come to Scotland they can struggle to cope with factors such as our high wind speeds, rapidly changing weather and complicated micro terrain. Things we consider normal but are outside the realms of their own experience. I can think of at least three visiting overseas experts who felt a bit lost trying to generate a forecast which properly interpreted the Scottish Highlandsâ unique weather and terrain. One stayed and after a season or two recalibrated his weather and avalanche mental database to the ânew normalâ.

The same applies to us forecasters here in Scotland visiting and working overseas. The mental shift required when dealing with a very different climate and much bigger, though possibly more homogenous, terrain cannot be overstated. (Iâm not referring to stability evaluations here but rather actual forecasting – two separate and different skill sets). The âshock of the newâ is humbling for a forecaster no matter how experienced. (See #6 below).

Putting aside the travails of the forecaster for a moment and thinking simply about avalanche weather and snowpack stability, all snow and weather conditions that depart by a very wide margin from normal are suspect as possible precursors to avalanching. A good example of this would be the winter of 2009/10. Huge surface hoar development had been widespread followed by strengthening easterly winds which stripped the surface hoar and dumped it on West-facing aspects. Here it was subsequently buried on top of, and close to, a layer of heavily facetted grains. These two layers – produced after exceptionally abnormal weather conditions for Scotland – induced a cycle of avalanche activity bigger in scale and geographical spread than I had ever seen here before. Exceptional weather and exceptional avalanches. See below:

(Above) Winter 2009/10. Exceptional weather. Huge surface hoar crystals development after an unprecedented clear, cold and still period. Photographed on the Carn Liath plateau in mid-February. Ski stick handle for scale. Was fantastic skiing on them, like when there’s really flattering corn (spring) snow! Not great for stability later though…

(Above) Winter 2009/10. Exceptional weather. Huge surface hoar crystals development after an unprecedented clear, cold and still period. Photographed on the Carn Liath plateau in mid-February. Ski stick handle for scale. Was fantastic skiing on them, like when there’s really flattering corn (spring) snow! Not great for stability later though…

(Above) Here are the surface hoar crystals on the plateau twinkling in the sunlight. Archive photo taken the same day as the previous shot.

(Above) Here are the surface hoar crystals on the plateau twinkling in the sunlight. Archive photo taken the same day as the previous shot.

(Above) The wind inevitably returned. Light to moderate easterlies stripped most of the surface hoar from the plateau and dumped it on SW to W aspects. These places already had a covering surface hoar and were sheltered from the wind plus had a layer of facets beneath, as shown in the photo. Subsequent snowfall/drifting buried all of this beneath slab up to 3m deep. Like a house built on sand it was never going to end well.

(Above) The wind inevitably returned. Light to moderate easterlies stripped most of the surface hoar from the plateau and dumped it on SW to W aspects. These places already had a covering surface hoar and were sheltered from the wind plus had a layer of facets beneath, as shown in the photo. Subsequent snowfall/drifting buried all of this beneath slab up to 3m deep. Like a house built on sand it was never going to end well.

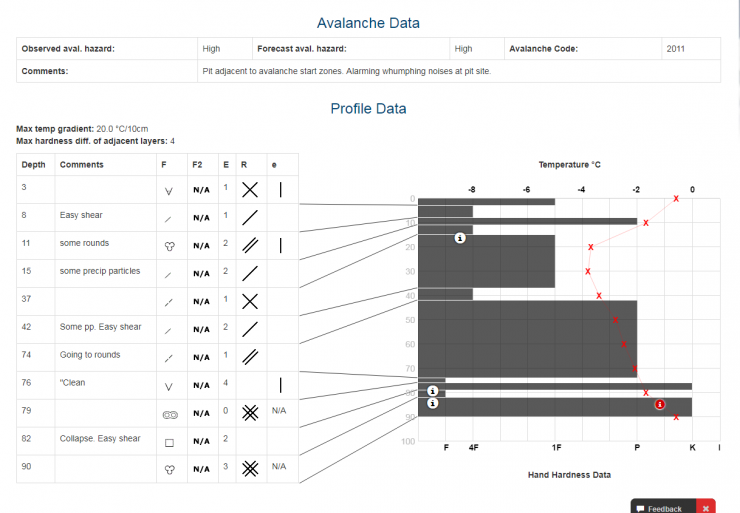

(Above) The formal snow profile produced on the day of the huge avalanches which slid on W and SW aspects. The pit was dug a few hours before the natural avalanches released. We’d been tracking the weak layers in these and similar places for some time and knew where the slide might occur, so the choice of our pit site was not co-incidental. Note the steep temperature gradients and the two weak layers at the bottom which show up in the previous shot.

(Above) The formal snow profile produced on the day of the huge avalanches which slid on W and SW aspects. The pit was dug a few hours before the natural avalanches released. We’d been tracking the weak layers in these and similar places for some time and knew where the slide might occur, so the choice of our pit site was not co-incidental. Note the steep temperature gradients and the two weak layers at the bottom which show up in the previous shot.

(Above) 1st March 2010 avalanches across the main Coire Ardair path. This one 400m wide. 4 people walking on the path ran away down hill after they heard a gunshot-like noise and saw the debris in transit. A narrow escape.

(Above) 1st March 2010 avalanches across the main Coire Ardair path. This one 400m wide. 4 people walking on the path ran away down hill after they heard a gunshot-like noise and saw the debris in transit. A narrow escape.

(Above) Crownwall approx 3m deep a little further along from the last photo. Photo taken the following day.

(Above) Crownwall approx 3m deep a little further along from the last photo. Photo taken the following day.

(Above) Main footpath in Coire Ardair was obliterated by debris.

(Above) Main footpath in Coire Ardair was obliterated by debris.

(Above)Â Debris up to 6m deep on the path. Several mature trees in the path of the avalanche were uprooted or snapped off and entrained in the debris flow.

(Above)Â Debris up to 6m deep on the path. Several mature trees in the path of the avalanche were uprooted or snapped off and entrained in the debris flow.

- Speed of change. (No one like change, least of all snow.)

An easy general rule. Snow doesnât like change; the faster the change, the less the snow likes it. In the words of the late Ed LaChapelle, âAny process that rapidly alters the mechanical or thermal state of the snow cover can lead to avalanching.â

Mechanical â sudden mechanical changes to the structure of the snow brought about by overloading it. Rapid loading by heavy snowfall, wind drifting, or people.

Thermal â rapid change, particularly if the trend is raising the snowpack temperature through 0 degrees C.. A sudden thaw immediately after recent snowfall/drifting is a common trigger, as is percolating water from unexpected rainfall. Snow is the weakest natural material and water is very good at weakening bonds within it.

Growth – Snow grains that grow at fast rates on the surface or within the snow can set the stage for future avalanching, namely surface hoar and facetted grains (or derivatives of the latter). Both are very weak in shear and can persist in the snowpack for a long time.

- Alterations to the exposed snow surface.

Alterations to the exposed snow surface tend to affect the bonding of subsequent snow and influence the likelihood of avalanching.

Most important alterations of the snow surface:

- Surface hoar

- Radiation re-crystallisation and near-surface facets

- Sun crust

- Rain crust

- Freezing rain or rime

- Wind crust

- âAre you local?â

The forecaster with local knowledge is in possession of a full deck of aces. Theyâll know all the âfrequent flyerâ avalanche paths (plus the not so well known ones), the weird terrain features and micro-climate, the strange local wind effects, the not so obvious shaded locations where facets grow, and the places to go and not to go when itâs really avalanchey. Anyone whoâs worked with snow in one small geographical area for a considerable period will understand the avalanche problem in that location like no-one else. (Also, see #3 above)

Today at Creag Meagaidh.

(Above) Stellar day. Good cover of snow remains on recent lee slopes (anything with East on it > E, NE, SE etc.) down to 450-500m in places.

(Above) Stellar day. Good cover of snow remains on recent lee slopes (anything with East on it > E, NE, SE etc.) down to 450-500m in places.

(Above) Less good cover on recent windward slopes. A West aspect on Na Cnapanan. 600m at the skyline above. A group of ‘Perspiring Adventurist’ ski-tourers from Glenmore Lodge linking together snow patches whilst making their way up to more complete cover on the Carn Liath plateau. Fair number of other folk out on skis today, too.

(Above) Less good cover on recent windward slopes. A West aspect on Na Cnapanan. 600m at the skyline above. A group of ‘Perspiring Adventurist’ ski-tourers from Glenmore Lodge linking together snow patches whilst making their way up to more complete cover on the Carn Liath plateau. Fair number of other folk out on skis today, too.

(Above) Looking into Coire Chomharsainn with the Creag Mhor ridge on the skyline. Top right skyline around 900m. East-facing and much better, more complete cover. Melt runnels on the snow surface show up well, the result of the meltdown a day or two ago.

(Above) Looking into Coire Chomharsainn with the Creag Mhor ridge on the skyline. Top right skyline around 900m. East-facing and much better, more complete cover. Melt runnels on the snow surface show up well, the result of the meltdown a day or two ago.

Comments on this post

Got something to say? Leave a comment

Grant Duff

21st February 2018 7:10 pm

As I seem to remember the 2010 avalanche was noted as being a very rare occurrence something like once in 100 years at that spot. Certainly the damage to the tree is still very evident today. Thanks for a very informative blog as usual.

meagaidhadmin

21st February 2018 10:02 pm

Glad you enjoyed the piece, Grant.

Kate Gilliver

21st February 2018 8:33 pm

Really interesting and informative read, many thanks! A week in Newtonmore starting this weekend, so a very timely piece on avalanches 🙂

meagaidhadmin

21st February 2018 10:02 pm

Hope you have a good week, Kate, though the weather looks like turning substantially more wintry (again!) later next week in the east. Will be best in the west, I think!

Rhys Jaggar

21st February 2018 8:47 pm

When I did Ski Club of GB training in Tignes in 1990, the local piste control showed us their avalanche maps with frequency and greatest distance avalanche has ever travelled at a particular site. They bedecked the walls in HQ….

Does SAIS/Glenmore Lodge/others maintain similar ‘maps’ for the main Scottish climbing areas and if so are there ways for the public to access them?

meagaidhadmin

21st February 2018 9:51 pm

A very good question.

No formal and/or published mapping of avalanche paths at the moment, Rhys. This was considered a year or two ago but it wasn’t thought necessary or appropriate for the six SAIS areas. In the Alps and North American Rockies avalanche paths are mapped by Highway departments, regional authorities (important when considering new housing developments in the mountains), mining companies operating in remote mountainous areas and heli-ski operators. There’ll be others, too. All because avalanches in those places can affect settlements, infrastructure and litigation (lawsuits against heli-ski companies, ski areas etc.).

In Scotland we have (almost) none of those issues. Also, we felt mapping our avalanche paths might induce mild panic/hysteria amongst our mountain users, or at least the less experienced ones! For example, most of Coire Ardair and its environs would be ‘painted red’ with avalanche paths, and of course no-one would ever walk up the main Coire Ardair path because large avalanches can run across it…..every hundred years or so. What about slopes that have never before had a recorded avalanche but could avalanche due to inclination/aspect/altitude. A “safe” place according to the avalanche map….but only until the avalanche dragon eventually decides to visit there. See where I’m going with this? Not sure mapping avalanche paths in this country would serve Scottish winter mountaineering and its participants in the way some might anticipate.

Also, did I mention the unpredictable effects of climate change on where future avalanches may run?…I could go on!

Many thanks for you comment.

roger clare

21st February 2018 9:07 pm

Very interesting and informative piece as always. Let’s hope the good conditions continue for a while yet. It’ll be interesting to see what happens next week with the easterlies!

meagaidhadmin

21st February 2018 9:56 pm

Re. Easterlies. The very useful MWIS weather outlook video published on Tuesday makes interesting viewing regarding this. A visit from the ‘Beast from the East’, for want of a better expression, is anticipated next week.

Many thanks for your comment.

Geoff

22nd February 2018 9:11 am

The avalanche ‘heat’ map on your website is useful to see most common areas reported/witnessed for avalanche activity.

meagaidhadmin

22nd February 2018 10:41 am

Agreed. Lets people know what’s been happening in the past 48hrs which is much more useful to mountain goers than fixed avalanche path mapping.

Thanks for your comment, Geoff.

Alasdair J

22nd February 2018 12:03 pm

Thanks for the very interesting and informative blog post! I enjoy following the reports from all the SAIS areas and find the whole subject fascinating. This question might be too broad to succinctly answer, but how does someone actually get involved in avalanche forecasting in the first place (if there even is such a thing as a ‘typical’ path)?

Thanks again and keep up all the good work!

Alasdair.

meagaidhadmin

22nd February 2018 12:55 pm

Germane question, Alasdair.

Unfortunately, you’re too late for the current avalanche forecaster training programme but have a look here for some general guidance:

https://www.sais.gov.uk/resources/forecaster-training-prog/

The SAIS instituted a training programme in order to ensure succession. This will not be a yearly recurring process since we are a very small workforce and personnel turnover is nil/negligible but may increase in a few years time.

*Note that this year’s successful candidates have entered a training programme and there is no guaranteed work at the end of it. The training programme takes a minimum of two winters but, as a pre-condition, all candidates will already have had many years experience looking at snow and dealing with avalanches.

I’m going to be producing a ‘Long Read’ before the end of the season which should shed at least a little light on the new cadre of trainees who’ve been inducted onto the Forecaster Training Programme.

Phil Marsh

22nd February 2018 3:48 pm

Many thanks for the very interesting blogs and this long read one now. Always an essential read.

meagaidhadmin

22nd February 2018 4:01 pm

Kind of you to say so, Phil.

Many thanks for your comment.

Facetious Crystals

23rd February 2018 9:45 am

Excellent piece complemented with great photos – Cheers!

meagaidhadmin

23rd February 2018 1:26 pm

Hey, Facetious!

We aim to please.

Many thanks for your comment.