Gimme shelter

17th February 2023

(Above) Looking west along Loch Laggan towards the eastern end of the Grey Coires. Whitecaps aplenty this morning at the tail end of Storm Otto; strong and blustery in Coire Ardair a little later.

(Above) Looking west along Loch Laggan towards the eastern end of the Grey Coires. Whitecaps aplenty this morning at the tail end of Storm Otto; strong and blustery in Coire Ardair a little later.

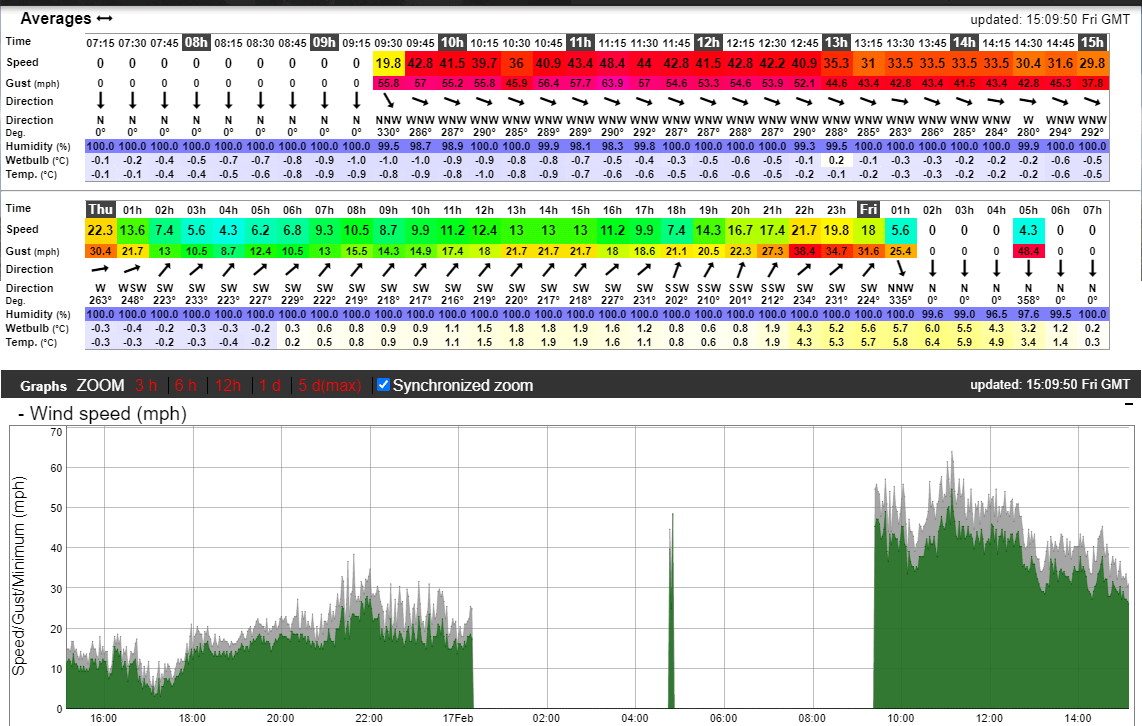

(Above) Temperature and wind data from the Creag Meagaidh weather station at 903m. The wind data went AWOL during the peak hours of the storm. We may need a beefier weather station!

(Above) Temperature and wind data from the Creag Meagaidh weather station at 903m. The wind data went AWOL during the peak hours of the storm. We may need a beefier weather station!

(Above) Coire Dubh viewed between showers from the A86. Persistent overnight rain and very mild temperatures induced some minor sluffing and cornice collapse action – as seen here – on some NE to E aspects.

(Above) Coire Dubh viewed between showers from the A86. Persistent overnight rain and very mild temperatures induced some minor sluffing and cornice collapse action – as seen here – on some NE to E aspects.

(Above) Looking across the steep rocky slabs of this east aspect of Sron a Ghoire, which is the mountain immediately in view when in the main car park. Debris from a minor full-depth avalanche (15m across, running out 30m) which slid during or immediately after the heavy rainfall that affected the area overnight and during the early morning. One of our ‘frequent flyer’ locations for this type of avalanche in certain weather conditions. It was a section of the dense, mature snowpack that took a trundle down the hill after its bed surface became super-saturated.

(Above) Looking across the steep rocky slabs of this east aspect of Sron a Ghoire, which is the mountain immediately in view when in the main car park. Debris from a minor full-depth avalanche (15m across, running out 30m) which slid during or immediately after the heavy rainfall that affected the area overnight and during the early morning. One of our ‘frequent flyer’ locations for this type of avalanche in certain weather conditions. It was a section of the dense, mature snowpack that took a trundle down the hill after its bed surface became super-saturated.

(Above) Looking for shelter. A Plas y Brenin group approaching the Inner Coire of Coire Ardair en route to the traditional snow hole site just beyond the summit of ‘The Window’, this well-known bealach. If they were unlucky enough to have to dig their own snow holes I hope they packed metal shovels. The snowpack is quite dense and moist with a developing crust and unlikely to succumb easily to manual excavation.

(Above) Looking for shelter. A Plas y Brenin group approaching the Inner Coire of Coire Ardair en route to the traditional snow hole site just beyond the summit of ‘The Window’, this well-known bealach. If they were unlucky enough to have to dig their own snow holes I hope they packed metal shovels. The snowpack is quite dense and moist with a developing crust and unlikely to succumb easily to manual excavation.

(Above) The NE facing crags of the Inner Coire of Coire Ardair during a break in the light snow showers. Just one of two residual old cornices in situ at the moment, such as the remnants above ‘Cinderella’ – top centre right of the photo. Quite a lot of old avalanche debris in the coire, most of it from the last avalanche cycle on 9th & 10th February.

(Above) The NE facing crags of the Inner Coire of Coire Ardair during a break in the light snow showers. Just one of two residual old cornices in situ at the moment, such as the remnants above ‘Cinderella’ – top centre right of the photo. Quite a lot of old avalanche debris in the coire, most of it from the last avalanche cycle on 9th & 10th February.

(Above) Evidence of recent rock fall this morning on the south-facing side of the Inner Coire – the righthand side of the photo. Hazard from this is expected to dissipate with the onset of persistently cooler temperatures. Meltwater and surface runoff had most of the burns running full today.

(Above) Evidence of recent rock fall this morning on the south-facing side of the Inner Coire – the righthand side of the photo. Hazard from this is expected to dissipate with the onset of persistently cooler temperatures. Meltwater and surface runoff had most of the burns running full today.

(Above) Looking across into Easy Gully on the Post Face of Coire Ardair. ‘Last Post’, one of Creag Meagaidh’s signature ice routes, was a full-on waterfall this morning – the watery cascade is visible midway up Easy Gully.

(Above) Looking across into Easy Gully on the Post Face of Coire Ardair. ‘Last Post’, one of Creag Meagaidh’s signature ice routes, was a full-on waterfall this morning – the watery cascade is visible midway up Easy Gully.

(Above) The Big Picture. L to R: Creag Mhor ridge, Puist Coire Ardair 1071m, Sron a Ghoire 1001m , the Post Face of Coire Ardair, The Window and part of Coire Chriochairein (sunlit). A thin dusting of fresh snow disguises the patchy nature of the old snow cover above 850m.

(Above) The Big Picture. L to R: Creag Mhor ridge, Puist Coire Ardair 1071m, Sron a Ghoire 1001m , the Post Face of Coire Ardair, The Window and part of Coire Chriochairein (sunlit). A thin dusting of fresh snow disguises the patchy nature of the old snow cover above 850m.

General snow stability improved a lot on Friday, the surface of the old snowpack becoming firm or hard at altitude by the end of the day.

There’s some snowfall in the forecast for Friday night and into Saturday morning, much of this arriving on light Easterly winds so will accumulate on bare ground on our (very few) steep West aspects. Elsewhere new soft weaker windslab on NW through N to NE aspects is anticipated to be localised in distribution, that is, confined to the top of lee slopes. The old exposed and scoured snowpack will be well-bonded and stable.

Comments on this post

Got something to say? Leave a comment

Keith Horner

17th February 2023 6:20 pm

Seems more like ‘I can’t get no satisfaction’ this winter…..! – high winds, low snowfall and almost tropical temperatures combining to significantly limit winter climbing potential – the torrent of water coming down Last Post and also off the slopes of Pinnacle Buttress is surely highly unusual in mid-February and a very worrying sight.

And another ‘full depther’ to add to your collection of avalanche porn. Do you think that the supersaturation of the snowpack bed resulted from the high temperatures recorded overnight or meltwater/surface water runoff from above gaining access at the top of the snow patch and acting as a lubricant between snowpack and ground surface – or possibly both? And I wonder if the ground surface temperature at the time of the initial snowfall plays a role – if the ground wasn’t frozen, would the snow cover seal in the higher temperature and act as an insulator, and that this could then contribute to softening the bond between the snow pack and the ground?

meagaidhadmin

17th February 2023 7:57 pm

Some good observations and pertinent questions, Keith.

Re. The bed surface temperature. First principles. Keep in mind that the layers of soil, sub-soil and bedrock move heat from near the centre of the earth outwards towards the surface. The bedrock and everything above it then stores and steadily releases that heat. For us – at our latitude with a mild maritime climate – that means the bottom of the snowpack is rarely below 0 degrees C. for any length of time.

(Different rules for higher latitudes with persistent, much colder air temperatures where permafrost is often a feature. See below.)

I quite often hear locals say the ‘snow will stay on the ground for weeks because there was a very hard frost before the snowfall.’ Simply not the case in the UK. The snow may linger for a while because of cold air temps after snowfall but what’s lying on the ground will be melting from the underside, from the ground upwards.

Of course, the ground can freeze and stay frozen for a time in the Highlands. I recall underground water pipes in Braemar freezing at a depth of 30″ and remaining that way for a couple of weeks but that was during prolonged very cold, clear weather with little snow cover on the ground. (Had there been snow cover then this may have insulated the ground from the effects of long wave radiation – the loss of heat to clear skies – and induced the ground to thaw! Local ‘Building Control’ officers in Badenoch & Strathspey encourage those building new houses to have their water pipes laid 1.2m down from the surface to guard against these occasional ‘deep’ freezes.) Massive digression. Apologies!

Rainfall and meltwater percolation through the snowpack and runoff into the snowpack/ground interface will be the means by which the bed surface is lubricated and glide encouraged, either slowly producing visible glide cracks + plastic deformation (buckling) of the snowpack. Or abruptly, giving an avalanche.

In the case of the small full depth event on Sron a Ghoire today, I would say it was a combination of very mild air temperatures (maxing out at 6.5 degrees C.) and persistent rainfall that produced the avalanche. The bed surface, I hazard, would have been a degree or two above freezing.

Bit rambling that, with a few tangents, but I hope I answered your questions!

BTW. ‘The Stones’ – definitely a fan!

Stan Wygladala

17th February 2023 10:29 pm

“Pleased to meet you, won’t you guess my name, but what’s troubling you is the nature of my game”.

Which is….when it is cold for a long time and snowing from November until February it’s a good time to climb in early March, which we did as the days were a bit longer. Meggie was solid with consolidated snow and ice. The glacier lake was so frozen we could jump on it. The Ben was a paradise. The north face was often very still and the cold froze in our nostrils. No ice fall then.

For your amusement……after many winter adventures went up the Ben in September and was amazed to find the summit shelter was about 15 ft in the air and…there were paths!!

Yourself and Keith, no offence intended, can interchange technical details re. snow conditions but it isn’t the real world as it once was.

We had some basic predictions. Stay on the ridges, don’t go near the cornices, never, ever go up the Hidden Valley in Glencoe etc etc. Don’t go up the North Face of the Ben in March if the sun is out etc etc..

Would really appreciate your comments, and Keith’s on my rambling!

Keith Horner

18th February 2023 11:30 am

Stan – as a certain B Dylan said ‘the times they are a changing…..’. Whilst I, like you, have many fond memories of fantastic winter climbing days when the polar continental high pressure system sat over Scotland for months, the reality is that we now live, whether we like it or not, in a changing world of radically different weather patterns. Whilst we of a certain generation can be nostalgic about past conditions, and be immensely thankfully that we were around at the time to experience and enjoy them, the real world of Scottish winter climbing now is about fickle, rapidly changing conditions and the need to be adaptable and to strike whilst the iron is hot (or rather whilst the ice is in…!) to maximise activity. Blogs like these and improved mountain weather forecasting are important supplements to the traditional rational route selection processes we used based on more limited information and understanding and allow a much more detailed appreciation of current snowpack and climbing conditions to be developed to assist making appropriate judgements in response to the more varied and unstable conditions which are being experienced on our mountains in winter.

BTW – Check out ‘That’s 60’s’ on the Smithsonian channel for some archive footage of live performances of many of the Stones classic tracks – the raw energy of the performances and the music is palpable even 50 years later….